WEST LAFAYETTE — Much of the space junk orbiting Earth won’t clean up itself – or tell you how it got there.

Purdue University’s Carolin Frueh and her team are investigating what causes spacecraft to become space junk. Their findings are revealing ways to prevent spacecraft from breaking apart into thousands of pieces of debris that pose a threat to space stations and satellites.

Since 1957, there have been more than 570 incidents of spacecraft fragmenting in Earth’s orbit because they exploded, detonated, or collided with each other.

Companies have begun testing technology that may help clean up the mess, but it’s not often clear how spacecraft fragment in the first place. Frueh’s team has undertaken the extremely complicated math needed to get answers.

“I like harsh, challenging problems that don’t have obvious solutions,” said Frueh, an associate professor in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “Because space objects are too far away to easily do experiments on or with them, we just observe these objects with a telescope. But even then, we don’t have much data on the objects, as they are not always visible or they’re too small to detect. The question is, ‘What can I still find out about this object with the little data that I can collect?’”

Unraveling the mystery behind a spacecraft’s explosion

Some of the biggest culprits of space debris resulting from fragmentation are the upper stages of rockets. The upper stage, which burns last in a mission, tends to stay in space after propelling satellites into orbit. U.S. spacecraft are recommended to deorbit within 25 years of end-of-mission, but not all comply.

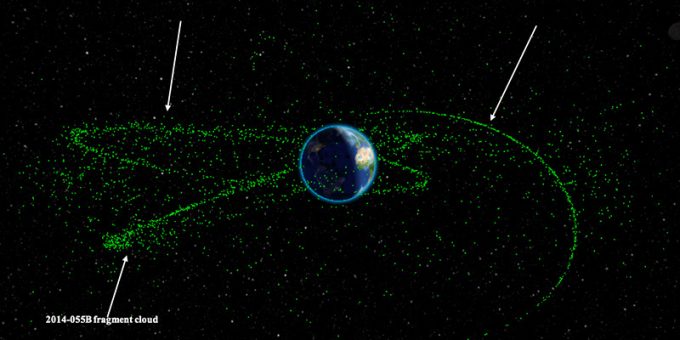

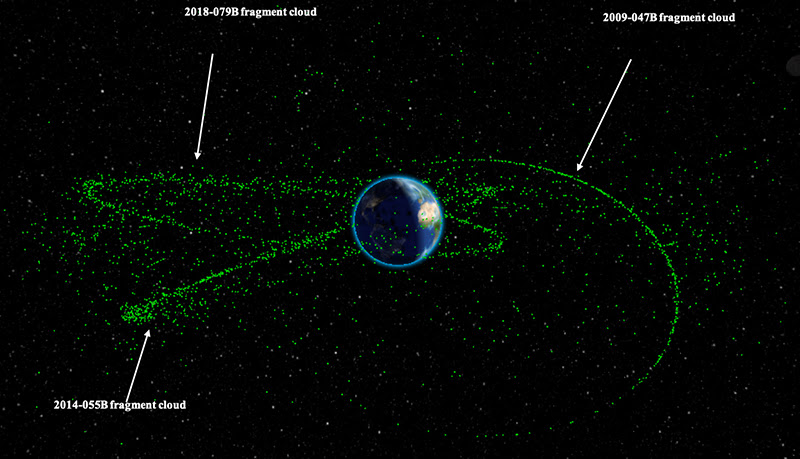

A spacecraft can shatter into hundreds of pieces – many the size of a quarter-inch or smaller. At altitudes of about 22,000 miles above Earth, Frueh and her collaborators track fragmentation pieces larger than six inches. The problem is speed: Space debris tends to travel faster than a bullet out of a gun (upwards of 15,000 mph). This speed makes even smaller pieces more harmful when they collide with other objects.

Purdue researchers and their collaborators identify what causes spacecraft to explode by performing computations with and processing available data on that spacecraft’s debris. (Carolin Frueh, Purdue University/Thomas Schildknecht, Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern) Download image

The more that researchers learn about how spacecraft fragment, the more obvious it becomes how complicated the underlying problem is – and, therefore, the math trying to describe it. In collaboration with the University of Bern in Switzerland, Frueh’s team discovered that identical upper stages apparently fragmented for different reasons.

Their study examined telescope data on three upper stages that had exploded in 2018 and 2019 after less than 10 years of being in space. Even though leftover fuel had allegedly been removed from these upper stages to prevent explosions, one upper stage likely fragmented because a clogged vent caused unused propellant to combust. Another upper stage had possibly experienced structural failure, causing it to implode, and a small piece of debris might have collided with the third upper stage.

The findings add to the challenge of figuring out how to prevent spacecraft from becoming junk.

“It’s interesting that there wasn’t just one cause that had determined the fate of all three upper stages,” Frueh said.

Frueh works with space agencies to improve databases of space objects, avoiding debris collision with their own satellites. Throughout the past year, she has helped the German Aerospace Center (DLR) enhance how its network of telescopes detects new objects, which are then cataloged in a database to aid collaborating owner-operators.

“These objects normally just look like white dots, similar to stars against a night sky. It can be hard to tell which ones are objects that you have already identified,” Frueh said.

Using sunlight to diagnose problems with spacecraft

It’s possible but very difficult, to detect problems with spacecraft before they cause an explosion. Even more challenging is determining characteristics such as the size, shape, and rotation of those objects.

Frueh is among only a handful of researchers using a technique called “light curves,” which can identify potential breakdown issues from thousands of miles away based on how that spacecraft or its components reflect sunlight.

The method calls for using telescopes on Earth to collect the light reflected by the object, such as a satellite. Changes in the brightness of the object’s white dot over time are recorded as light curves. These light curves are then processed and used to extract information about an object’s appearance or rotational state.

“It is like driving a car, where you can’t get out of the car to check if something has fallen off or gotten damaged. But you know that there might be a problem,” Frueh said. “An operator might notice that a satellite appears unstable or not charging properly. An outside perspective can tell if it’s because something broke off, or if a panel or antenna is not properly oriented, for example.”

Information that light curves provide about satellites also could improve how they are designed in the future. Frueh’s lab has identified objects orbiting Earth that appear to be the gold foil of satellites flaking off over time. These flakes are hazardous but very difficult to track.

The next frontier: a junk-free moon orbit

Only a few spacecraft are in orbits around the moon. But if the space junk problems surrounding Earth are repeated in the moon’s orbits, human space exploration could be at risk.

Frueh and her collaborators are working to establish engineering methods that would keep the cislunar space – the region encompassing Earth and the moon – free of space debris before the spacecraft in that region begin to fragment.

“There’s starting to be a lot more traffic in the cislunar space. We want to avoid some of the haphazard approaches we’ve done around Earth that clogs up everything,” Frueh said. “In a region where the dynamics are very different, what does that mean for space debris? Where are spacecraft going after a mission ends? How do we establish observations from that space to track objects? The goal is sustainable use of space.”

Frueh’s research is funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, NASA, the Air Force Research Laboratory, the Universities Space Research Association, the German Aerospace Center, and the European Space Agency. This research also is financially supported by national and international private companies and NASA contractors such as The MITRE Corp., Thales Global Services SAS, Analytical Graphics Inc. (AGI), Applied Optimization Inc., McGraw and Associates LLC, and Rhea Space Activity.

Information Kayla Wiles, wiles5@purdue.edu

Source: Carolin Frueh, cfrueh@purdue.edu